1. Introduction

Recently we have studied and discussed the unusual optical properties of the Veil of Manoppello [

1,

2], on which the face of Jesus Christ (Holy Face) is impressed. Several authors [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10] have suggested that the image of the face on the Veil of Manoppello is superimposable to the image of the face of the Man of the Turin Shroud, a linen cloth indelibly impressed by the complete front and back images of a human body [

11]. According to the Catholic tradition, it is the burial cloth in which Jesus of Nazareth was wrapped after his death. The present paper focuses on assessing whether the two images can be superimposed, i.e., whether they are different images of the same face. Indeed, any correlation between the two images of the face of Jesus would raise the question of their historical relationships.

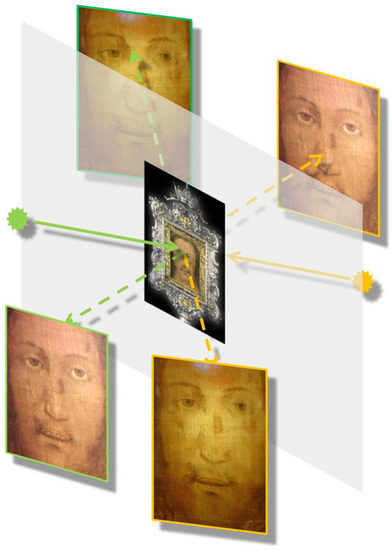

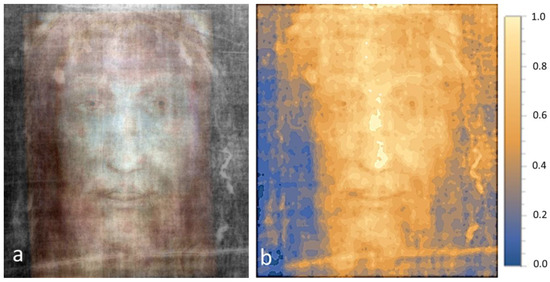

The Veil of Manoppello is a rectangular canvas of 240×175 mm2. Its particular characteristic is being semitransparent. The face is visible on both sides (front–back) and, depending on the lighting and observation conditions, shows some differences in the anatomical details, as schematized in . An analysis of the Veil has allowed us to clarify some aspects of the possible physical mechanism underlying its unusual optical behavior. It is a linen fiber fabric consisting of very thin threads, with a thickness of about 0.1 mm, separated by distances even twice the thickness of the threads, so that about 42% of the Veil is empty space. The fibers of the linen threads have been likely cemented by an organic substance of chemical composition similar to cellulose, presumably starch, therefore eliminating the air between them. Such a structure causes the optical behavior of the medium to be intermediate between that of a translucent medium (cemented linen threads) and that of a transparent one (empty space between the threads).

Figure 1. Image of the face visible on the Veil of Manoppello according to different lighting conditions: green, image lit by a light source located in front of the Veil; yellow, with the source located in the back.

Since the face is deformed due to distortions of the meshes of the Veil, caused by the yielding of the very fine structure of the fabric, first we have tackled the problem of digital image restoration to correct the face deformations which, in some regions of the image, are even about 1 cm [

1]. Afterwards, we have performed a spectral analysis of the transmitted image [

2]. As evidenced in the first study, its thin linen threads are translucent, presumably because it is starched, and light passes through them. As a result, the yellowish color of the ancient linen and starch contribute substantially to the final hues of the face, especially when the Veil is lit from the backside with grazing light. Spectrophotometry measurements show how the fabric absorbs the various chromatic components. Through these quantitative evaluations, the colors of the transmitted face image have been compensated, by subtracting the contribution due to the yellowish coloration of the thin linen threads.

Furthermore, the rotational spectrum of the image has been studied after digital restoration [

2]. The linear fit of the power spectrum in bi-logarithmic scale with a power law

fP provided a surprising value for the slope parameter

P=−3.49±0.03. This result was unexpected because it is typical of photographs of human faces, not of portraits of human faces painted by artists, which instead have statistical properties of fractal type, with slope’s values

P=−2.0.

The Turin Shroud has been in the center of a lively scientific debate since the end of the XIX century, when the negatives of its photographs, taken by S. Pia in 1898, clearly showed the impressed image of a man. After carbon-14 dating [

12] of a linen piece taken from a corner of the Turin Shroud, the scientific controversy regarding its authenticity exploded. Indeed, the medieval date, derived from carbon-14 analysis, is not compatible with the hundreds of data that, conversely, show the Turin Shroud is compatible with the historical period in which Jesus of Nazareth lived in Palestine, 2000 years ago [

13,

14]. Moreover, the carbon-14 dating results remain controversial [

15,

16], especially because of the likely non-negligible carbon contamination of the textile. This contamination can be due to many factors, including environmental ones [

17,

18]. Furthermore, a regression analysis on data of the Shroud’s carbon dating has shown their statistical heterogeneity, together with an implausibility of spatial allocations of some measurements’ samples [

16]. It should be also noted, however, that five different independent methods agree in assigning the age of the Shroud to the first century Anno Domini (AD). Indeed, the spectrometric methods, based on FT-IR/ATR (Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy/Attenuated Total Reflectance) and Raman spectroscopy, dates the Shroud to 300 Before Christ (BC) ± 400 years and 200 BC ± 500 years, respectively [

19]. The mechanical multi-parametric method, based on the analysis of five parameters, including the breaking load and Young’s modulus and the loss factor, after an adequate calibration based on the results of two dozen samples of known age, assigns the Turin Shroud to the years 400 AD ± 400 years [

20]. Another chemical method, based on estimates of the kinetic constants for the loss of vanillin from lignin, attributes the Shroud an age in the range 1300 to 3000 years [

21]. Finally a numismatic method [

20], based on the comparison between the Shroud and the effigies of Christ reproduced on Byzantine coins, shows that the Relic was well known in the Byzantine Empire since 692 AD.

Several hypotheses have been proposed regarding the formation of the body image on the Turin Shroud, and several experiments have been performed for this purpose, but none of them has been successful in reproducing, both at macroscopic and microscopic levels, all the characteristics of the image. A critical compendium of the hypotheses and the experiments performed can be found in [

22].

As already mentioned, some attempts to match the two images, namely the face visible on the Veil of Manoppello and the face of the body visible on the Turin Shroud, have already been attempted [

3,

10]. In particular, it was proposed that both images were formed in the same time, when the two fabrics were laying one upon another in the sepulcher where the body of Jesus Christ was deposed [

3]. It is beyond the scope of the present work to discuss the origin of the two images. In fact, we want to assess the possible presence of correlations between the two images and realize whether they may be related to the face of the same man. If these correlations were found, it would imply a possible interdependence of the two images of the Holy Face, useful to reconstruct the historical route of the iconography of the most represented face in the world, that of Jesus Christ. In none of the previous attempts to superimpose the two images, however, the deformations of the Veil of Manoppello were corrected before the comparison. As we have corrected them in our first work [

1], we think that the two faces, now, can be reliably compared with the aim of understanding whether the images are related, whether they belong to the same man, and obtaining, if possible, some additional information about their origin.

After this Introduction, in

Section 2 we show that the logarithmic transformation of the intensity of the Turin Shroud image, measured both with visible light and Ultra-Violet (UV) radiation, highlights some interesting anatomical details, such us the cheeks’ profiles. In

Section 3, after [

1,

2], we further analyze the face visible on the Veil of Manoppello. In

Section 4, we compare and match the two faces and, finally, in

Section 5 we discuss the results and in

Section 6 we draw some conclusions.

4. Comparison between the Faces of the Turin Shroud and the Manoppello Veil

As mentioned, some scholars have tried to match the face visible on the Veil of Manoppello to the face of the Man visible on the Turin Shroud [

3,

10]. However, as already noted, these scholars did not eliminate the distortions due to the yielding of the Veil fabric before doing the comparison. Indeed, as shown in [

1,

2], it is possible to highlight a consistent yielding of the Veil fabric, up to about 1 cm in some areas.

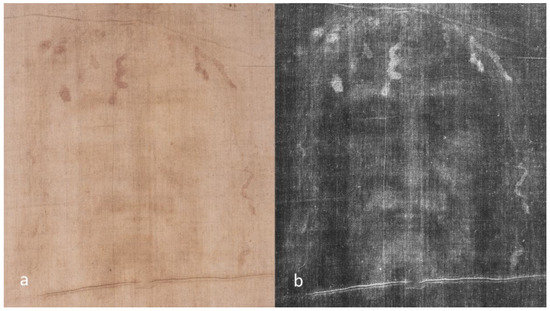

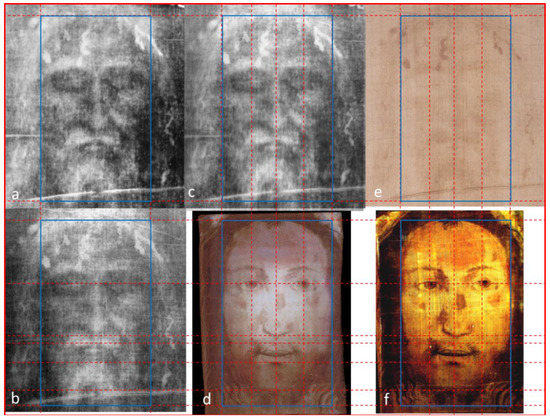

In a we show the face of the Turin Shroud visible with UV, after having applied the logarithmic transformation, corrected the stripes of the background [

23], and de-noised the final result. In b the same digital restoring procedure is applied to the face of the Turin Shroud seen with visible light. In c we averaged a,b, after having co-registered each other by aligning the hematic traces and the extended tissue defects, for example the long fold on the beard present in both images. d shows the digitally−restored Manoppello face. e shows the original photograph of the region of the face of the Turin Shroud. f shows the original photograph of the Veil of Manoppello (back side), taken by the third author, with the contrast enhanced. In each image the blue rectangular box defines the region of the face. The dashed horizontal and vertical red lines are drawn, for reference, in correspondence of some main anatomical details. All the images are shown in the same spatial relative scale, in a ratio 1:1.

Figure 5. (a) Turin Shroud face visible with UV. (b) Turin Shroud face seen with visible light. (c) Averaging of a,b. (d) Digitally restored Manoppello face. (e) Original photo of the Turin Shroud linen cloth, in the region of the face. (f) Original photo of the Veil of Manoppello (back side), with the contrast enhanced.

From the above figures it is important to note that the Face of the Turin Shroud and the digitally restored face of the Veil have the same proportions. Because the red dashed lines intersect the main anatomic details, any ratio between distances in the two images is the same, within an uncertainty related to the spatial resolution of the Turin Shroud image, equal to 4.9 ± 0.5 mm [

26]. For example, the ratio between the distance of the eyebrows’ center to the end of the nose, and the eyes’ distance is equal to

1.21±0.05 for the Turin Shroud and

1.23±0.05 for the face on the Veil. For the Turin Shroud the uncertainty, due to the spatial resolution, on distances of the order of 10 cm is about 5%. For the digitally restored face, visible on the Veil, the image is more detailed, but the Veil has a semi-transparent structure because its threads are separated by spaces up to twice their thickness. Thus, the resolution of the face visible on the Veil is related to its discrete structure, and can be set equal to the period of the threads. In [

2] we showed that, from the distance of the secondary Fast Fourier Transform peaks from the main maximum, it is possible to obtain information about the spatial periodicity of the weft and warp of the fabric, equal to

0.339±0.005 mm and

0.395±0.005 mm, respectively. Thus, the best resolution of the image can be set equal to the minimum of the local periodicity of the vertical threads, equal to 0.339 ≈ 0.34 mm. Therefore, for the face, the uncertainty on distances of the order of 10 cm is about 3.4%, due to the discrete structure of the threads. Therefore, within a maximum uncertainty of about 5%, the face of the Turin Shroud and the digitally restored face visible on the Veil are characterized by the same proportions and distances between the anatomical details. This finding is particularly evident if we compare the cheeks’ profiles of c, where both the left and the right cheeks are well visible, with those of d. It should be stressed that in the original Turin Shroud image, namely the image visible before the invention of photography, the face is much narrower. Thus, if we compare e with f, a great difference in the face width is particularly evident, well beyond the maximum uncertainty of 5%.

Conversely, as it is evident by comparing the blue boxes of c,d, the two faces, displayed in the same relative scale, are well proportioned regardless the slightly different perspective of the two images. Indeed, the Turin Shroud face seems to be slightly rotated to the right, while the Manoppello face seems to be slightly rotated to the left.

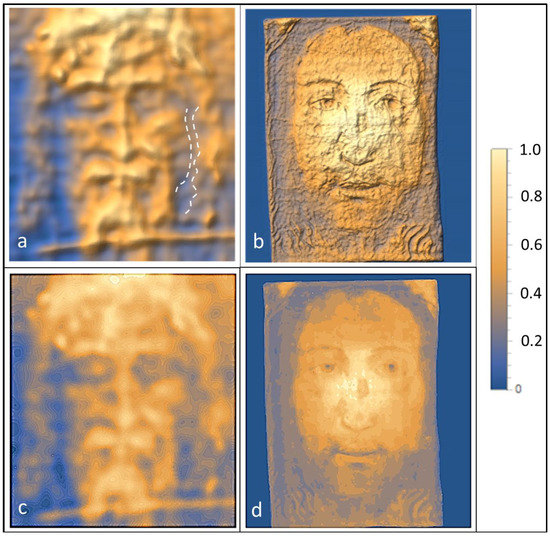

Furthermore, in some relief and contour plots, realized with the software Wolfram Mathematica, allows us to visualize the well-known fact that the image of the Shroud contains 3D features, for example with the nose in relief with respect to the other parts of the face. Before calculating the 3D plot relief, the image has been suitably binned by a factor 10×10 and smoothed with a bilateral filter of the software Wolfram Mathematica with spatial width of 10 pixels, to leave the principal anatomic details, because the spatial resolution of the initial image is only about 0.5 cm. Indeed, the original image was 5310×4744 pixels, to which corresponds an area of about 25.5 × 23.0 cm2. Thus, any pixel corresponds to a surface of about 0.05×0.05 mm2. The binning 10×10 leads to a binned pixel 0.5×0.5 mm2. Thus, the smoothing due to the bilateral filter on 10 binned pixels, i.e., on an area of 5×5 mm2, can be directly related to the image spatial resolution.

Figure 6. (a) Relief plot of the Turin Shroud face shown in the previous figure (panel 5b). (b) Relief plot of the Manoppello face visible in the previous figure (panel 5d). See main text for more details. (c) Contour plot of the Turin Shroud face shown in b. (d) Contour plot of the Manoppello face visible in d.

Differently from the Turin Shroud, the relief plot of the face visible on the Manoppello Veil partially lacks tri-dimensionality.

The graininess of the plot relief shown in b could be related to the semi-transparency of the Veil, leading to local maxima of transmitted light among the threads. It is interesting to note that in the Turin Shroud face it is slightly visible the profile of the right cheek, highlighted by a dashed white curve in a, separated by the profile of the hairs, also highlighted with another dashed white curve. The right cheek appears as it was swollen. It should be noted that also in the face of Manoppello, shown in b, it is visible a swollen right cheek.

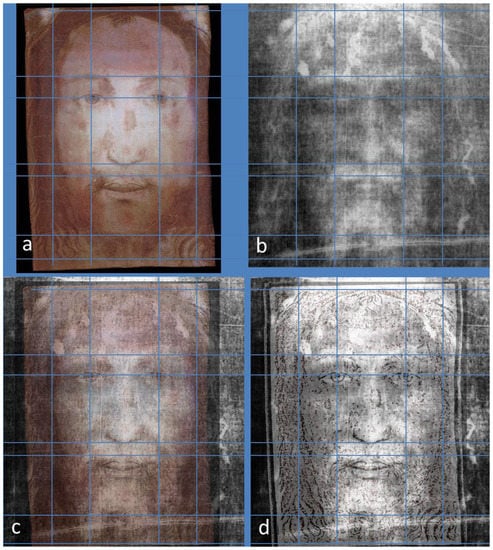

In we superposed the digitally restored face visible on the Veil (a) to that visible on the Shroud, after the logarithmic transformation of the intensity, the correction of the background stripes and de-noising the final result (b).

Figure 7. (a) Digitally-restored Manoppello face. (b) Turin Shroud face seen with visible light. (c) Averaging of 50% of a and 50% of b. (d) Averaging of the anatomical face profiles of a with b.

The result of the superposition of 50% of a and 50% of b is shown in c, aligned with the Turin Shroud image by centering the eyes’ regions. In d we have extracted the face profiles from a, by increasing 100% both the image contrast and sharpness, and by reducing the grey levels until leaving only the most intense image variations. Then, we have added it to b, to further investigate and assess the matching of the two faces.

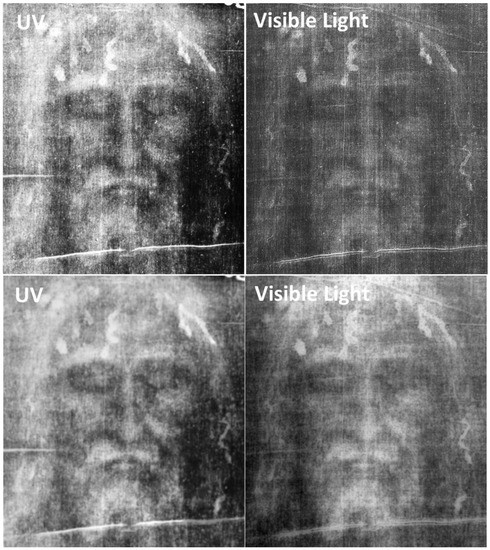

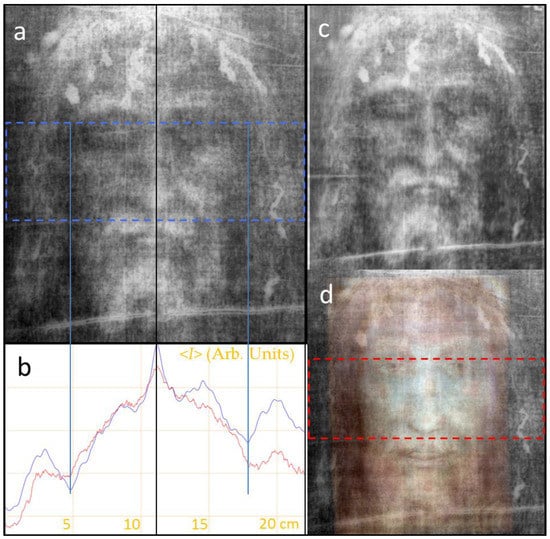

To be more detailed, in a we show the logarithm of the intensity with removed background stripes. In b we report the average ⟨I⟩ of the rows of a in the blue box of a (blue profile) together with the average ⟨I⟩ of the rows of c in the green box (green profile), where c shows the intensity without removed background stripes, together with the average ⟨I⟩ of the rows of d in the red box (red profile). The vertical blue lines intersect the two minima in the blue profile corresponding to the cheeks’ width for a. The vertical green lines intersect the two minima in the green profile corresponding to the cheeks’ width for c.

Figure 8. (a) Logarithm of the intensity with removed background stripes. (b) Blue profile: average of the rows of a in the blue box; green profile: average of the rows of c in the green box. (c) Intensity without removed background stripes. (d) Digitally-restored Manoppello face. (e) Positive image of the Turin Shroud.

Let us note that the width of the cheeks is underestimated in c by about 1.8 cm with respect to a, well beyond the finite image resolution of about 0.5 cm, if we do not remove the vertical background stripes and do not calculate the logarithm of the intensity.

By comparison, in d we show the digitally restored face of Manoppello compared with the positive image of the Turin Shroud (e). The relative distance of the green and blue vertical lines is the same of a–c, obtained by the minima of the averaged profiles shown in b. Let us note that the face cheeks’ width of d agrees well with the face cheeks’ width of a, as it can be also evaluated by comparing the red average profile, measured in d with the blue average profile measured in a. Conversely, by using the positive Turin Shroud image (e), the estimated cheeks’ width would be also smaller than what is obtainable in c; i.e., by the negative image. In other words, if the face size is calculated by direct inspection of e the underestimation of the cheeks’ width would also be more than 14%, as it can be evinced by the vertical blue and green lines used as a reference for a,c–e. Therefore, the digital restoration of the two faces seems to be a pre-requisite before comparing them, otherwise systematic errors in the determination of the cheeks’ widths would be unavoidable.

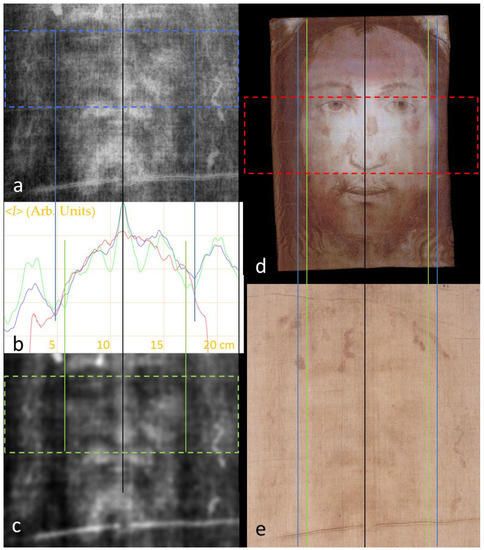

As a final combination of the face of the Turin Shroud and the face of the Manoppello Veil we can apply the Fourier synthesis. In this technique, instead of combining the two images in direct space, they are combined in the dual space. To perform this task, it is sufficient to calculate the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) of the two images, each of which gives a bi-dimensional function of the amplitude and of the phase. In their combination in the dual space we could use the amplitude of an image and the phase of the other. However, the phase function contains much more information than the amplitude function. Therefore, using either the phase of the FFT of the Turin Shroud face or that of the FFT of the Manoppello face, will lead to a dominant role of one of the two images in the final Fourier synthesis. To avoid this dominance, we can use a linear combination of phase and amplitude of both images. Then, to obtain the final Fourier-synthesis image, it is sufficient to calculate the inverse FFT of the combined FFT of the two initial images and keep either the real part or, almost equivalently, the absolute value. The amplitudes have been taken by a linear combination of the FFT of a (Manoppello face) and b (Turin Shroud face), with weights equal to 2/3 and 1/3, respectively; while the phase values have been taken by a linear combination of the FFT of a,b, but with complementary weights with respect to amplitude, thus equal to 1/3 and 2/3. Thus, for the amplitudes the weights are (2/3, 1/3), for the phases they are (1/3, 2/3), where the first value refers to the Manoppello Face FFT and the second to the Turin Shroud face FFT. The particular value 2/3 has been chosen for the following reasons. As previously discussed, the spatial resolution of the face visible on the Veil is limited by the discontinue fabric, with minimum distance between the threads equal to about 0.34 mm. In the case of Turin Shroud image the fabric is more continue. Indeed, although the image resolution is about 5 mm the pixel size can be chosen much smaller.

We have already verified that the Turin Shroud face image, analyzed in this work, has a pixel size of about 0.05 mm. However, it is characterized by a spatial resolution such that also a pixel binning of a factor of 10 does not worsen the visible anatomic details. The ratio of 0.34 mm for the Manoppello face and the 10-binned pixel size, equal to about 0.5 mm, for the Turin Shroud face, is 0.68, i.e., close to 2/3. Therefore, this choice of the weights includes in the composite image both the higher resolution amplitudes contained in the Manoppello face FFT, and preserves the anatomic details visible on the Veil up to their better spatial resolution, and the 3D information contained in the Turin Shroud FFT phases. Thus, after the linear combination of FFTs, we can calculate the inverse FFT to obtain the composite image. The final image obtained is shown in a. Notice that the weights (0.5, 0.5) for both amplitudes and phases in the Fourier synthesis would have given the same final image that is obtained directly by adding the two images without any Fourier synthesis. On the other hand, the weights (1.0, 0.0) for amplitudes and (0.0, 1.0) for phases, or vice versa, would have given the dominance of one image on the other.

Figure 9. (a) Fourier synthesis between a,d. (b) Contour plot of a. See main text for more details.

Returning to the final image, shown in a, b shows its contour plot. By comparing b with c,d it is evident that the new image contains 3D information and some anatomic details of both the Turin Shroud face and the Manoppello face, but combined in a different way with respect to c, the latter obtained by the most common direct average of the two faces, or, which is the same, by performing a Fourier synthesis with weights equal to (0.5, 0.5).

If we compare the average intensity profiles ⟨I⟩ of the rows of a (Turin Shroud’s face, blue profile) and of a (combined image in the FFT dual space, red profile), in the regions corresponding to the blue and red rectangular boxes of a,d, respectively, we obtain the result shown in .

Figure 10. (a) Logarithm of the intensity with removed background stripes. (b) Blue profile: average of the rows of a in the blue box; red profile: average of the grey levels of the rows in the red box of d, obtained by the Fourier synthesis. (c) Average of UV and visible Turin Shroud images. (d) a, obtained by the Fourier synthesis.

From the comparison between the two profiles of b with the red one shown in b we can see how that corresponding to the face of Manoppello (red profile of b) has not an evident maximum of intensity in correspondence of the nose, in the center of the plot. Conversely, the red profile of b, corresponding to the combined image, shows the presence of an evident maximum in correspondence of the nose. Moreover, by comparing c and b it is interesting to note that the cheeks’ profiles are more evident when we combine the UV and the visible light measurements (c), are even more delineated after the Fourier synthesis of the Turin Shroud face, seen with visible light, with the digitally restored Manoppello face.

5. Discussion

We have shown that, within a maximum uncertainty of 5%, the face of the Turin Shroud and the digitally restored face visible on the Manoppello Veil are characterized by the same proportions and distances between their anatomical details. With this regard, it should be stressed that in the original Turin Shroud image, namely the image visible before the invention of photography, the face is much narrower, well beyond the maximum uncertainty of 5%. Let us remark that the face visible on the Turin Shroud studied in this paper has been obtained by calculating the logarithm of the image intensity and by correcting the background. This digital procedure, never done before, has allowed seeing quite clearly the cheeks’ profiles, after the background stripes’ correction, as shown in for both the UV and visible light images. Now, the cheeks’ profile of the Turin Shroud face and that of the digitally restored Manoppello face are very similar, as evidenced both by the blue rectangular box in and by the image average profiles shown in . Thus, the digital restoration of the two faces is a fundamental prerequisite before their comparison because, otherwise, systematic errors in determining the cheeks’ widths would be unavoidable.

Further correlations between the two faces are also noticeable, such as the swelling of the right cheek. However, there are some evident differences, for example the “epsilon” blood trace on the forehead, visible only on the face visible on the Turin Shroud. This difference may be due to the fact that the image of the Manoppello Veil, according to tradition, was allegedly impressed during the uphill to Calvary when a woman, known as Veronica, offered a veil to Jesus to wipe his face, while the Shroud image was impressed later in the sepulcher. Therefore, the typical reversed “3” wound on the forehead may have been formed in this time interval. The moustache between the nose and the mouth seems to be different in the two cases, also for the fluids leaked by the nasal cavities of the corpse wrapped in the Shroud that could have affected locally the image formation process.

B. Paschalis Schlöemer has suggested that both the Turin Shroud and the Manoppello Veil images have been formed in the same time, with the two fabrics laying one on another [

3]. This is not our opinion. In fact, by taking into account all the above mentioned differences, it seems more reasonable to conclude that the two images were not impressed at the same time. Indeed, as shown in , the Turin Shroud face seems to be slightly rotated to the right, while the Manoppello face seems to be slight rotated to the left. Moreover, the latter shows the mouth slightly open, while the Turin Shroud face shows the mouth completely closed.

Differently from the Turin Shroud, the relief plot of the face visible on the Manoppello Veil () shows some lacks of tri-dimensionality, in particular in correspondence of some anatomic parts characterized by smaller intensities due to their own color, such as the pupils, hairs, and beard. Also, the nose is flattened with respect to the cheeks. The contour plots of the Turin Shroud face drawn in c,d show that the maximum intensity of the nose is found at its end. Conversely, in the face there is a region around the nose characterized by higher values of the intensity. This finding could be related to the fact that the fabric of the Veil is semi-transparent and, very likely, in correspondence of the central region of the face, seen in transmission, more light has gone through the Veil, leading to a lack of correct tri-dimensionality in the region.

However, the different tri-dimensional content of the two images could be also related to the fact that the Turin Shroud body image is not a painting, even if the chemical/physical process of image formation is not yet assessed [

22]. Indeed, the Turin Shroud body image color depends only on a physical/chemical reaction of the outermost layer of the linen fibers compositing it. Traces of human blood are also imprinted on the Turin Shroud but they are not present in the other images, indicated by Catholic tradition as acheiropoietos, i.e., not made by human hand (Tilma of Guadalupe, Veil of Manoppello, some handkerchiefs of St. Pio from Pietralcina, and so on), with the exception of the Sudarium of Oviedo, which has no images [

20]. While for the other acheiropoietos images we do not know if they have actually been in contact with parts of a human body, for the Turin Shroud we are sure that it was put on a corpse, in a way to touch the tip of the nose and leave a free distance between nose and cheeks. Therefore, the image of the tip of the nose is the most clearly represented on the Shroud, leading also to tri-dimensional information embedded. Instead, even if we assumed that also the image on the Manoppello Veil was formed by contact, we should consider that its fabric is much softer, so that, if it was used to wipe the face of Jesus Christ during his Calvary, it touched his eyes and mouth for a moment and must have rubbed both sides of the nose. Therefore, differently from the Turin Shroud image, on the Veil one should expect clearer and sharper images of the eyes and mouth, and a more diffuse and large image of the nose. Nevertheless, tri-dimensional information can be transferred from the Turin Shroud face to that visible on the Manoppello Veil, through the Fourier synthesis approach, as shown in the and .

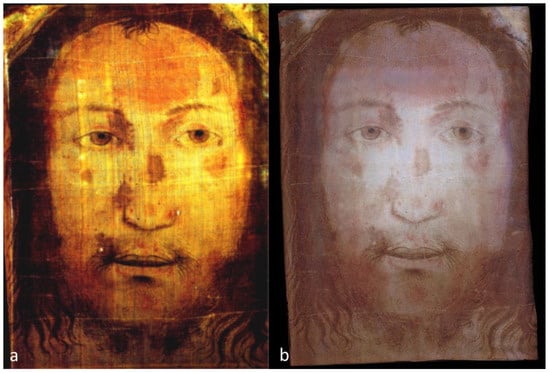

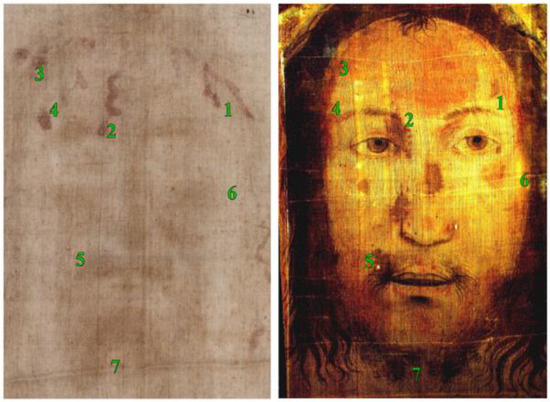

Finally, under the hypothesis that both the Turin Shroud and the Manoppello Veil are related to the same man, Jesus Christ, we can further compare the two images by considering the red stains that should be related to his Passion, described in the Gospels. In comparing them, however, we must remember that our analyses indicates that the two images correspond to different times of his Passion. The Shroud image formed in the sepulcher when the linen sheet wrapped a bloody dead man, whose blood crusts were transposing on the fabric during a fibrinolysis process. The face on the Manoppello Veil formed when Veronica used her veil to clean Jesus’ face, just before the crucifixion. Nevertheless, even if the two images correspond to different moments, we can find many similar details, especially those relative to the bloodstains. With reference to , we can find, among others, several congruence points between the two images.

Figure 11. Some congruence points detected between the Shroud face (left) and the Manoppello Veil (right). Legend: 1. Blood leakage probably due to a thorn of the crown; 2. Blood leakage probably due to a wound on the left eyebrow; 3. Blood leakage probably due to a thorn of the crown; 4. Blood leakage probably due to a wound on the left temple; 5. Blood on the left moustache probably due to a blow; 6. Swollen right cheek probably due to a club; 7. Bipartite beard.