The Via Dolorosa (Latin for “Sorrowful Way”, often translated “Way of Suffering”; Hebrew: ויה דולורוזה; Arabic: طريق الآلام) is a processional route in the Old City of Jerusalem, believed to be the path that Jesus walked on the way to his crucifixion. The winding route from the former Antonia Fortress to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre — a distance of about 600 metres (2,000 feet) — is a celebrated place of Christian pilgrimage. The current route has been established since the 18th century, replacing various earlier versions. It is today marked by nine Stations of the Cross; there have been fourteen stations since the late 15th century, with the remaining five stations being inside the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

Portals: Christianity Bible

The Via Dolorosa is not one street, but a route consisting of segments of several streets. One of the main segments is the modern remnant of one of the two main east-west routes (Decumanus Maximus) through the Roman city of Aelia Capitolina, as built by Hadrian. Standard Roman city design places the main east-west road through the middle of the city, but the presence of the Temple Mount along much of the eastern side of the city required Hadrian’s planners to add an extra east-west road at its north. In addition to the usual central north-south road (Cardo Maximus), which in Jerusalem headed straight up the western hill, a second major north-south road was added down the line of the Tyropoeon Valley; these two cardines converge near the Damascus Gate, close to the Via Dolorosa. If the Via Dolorosa had continued west in a straight line across the two routes, it would have formed a triangular block too narrow to construct standard buildings; the decumanus (now the Via Dolorosa) west of the Cardo was constructed south[dubious – discuss] of its eastern portion, creating the discontinuity in the road still present today.[citation needed]

The first reports of a pilgrimage route corresponding to the Biblical events dates from the Byzantine era; during that time, a Holy Thursday procession started from the top of the Mount of Olives, stopped in Gethsemane, entered the Old City at the Lions’ Gate, and followed approximately the current route to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre; however, there were no actual stops during the route along the Via Dolorosa itself. By the 8th century, however, the route went via the western hill instead; starting at Gethsemane, it continued to the alleged House of Caiaphas on Mount Zion, then to Hagia Sophia (viewed as the site of the Praetorium), and finally to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.

During the Middle Ages,[dubious – discuss] the Roman Catholics of Jerusalem split into two factions, one controlling the churches on the western hill, the other the churches on the eastern hill;[dubious – discuss] they each supported the route which took pilgrims past the churches the faction in question controlled, one arguing that the Roman governor’s mansion (Praetorium) was on Mount Zion (where they had churches), the other that it was near the Antonia Fortress (where they had churches).

In the 14th century, Pope Clement VI achieved some consistency in route with the Bull, “Nuper Carissimae,” establishing the Franciscan Custody of the Holy Land, and charging the friars with “the guidance, instruction, and care of Latin pilgrims as well as with the guardianship, maintenance, defense and rituals of the Catholic shrines of the Holy Land.” Beginning around 1350, Franciscan friars conducted official tours of the Via Dolorosa, from the Holy Sepulchre to the House of Pilate—opposite the direction travelled by Christ in Bible. The route was not reversed until c. 1517 when the Franciscans began to follow the events of Christ’s Passion chronologically-setting out from the House of Pilate and ending with the crucifixion at Golgotha.

From the onset of Franciscan administration, the development of the Via Dolorosa was intimately linked to devotional practices in Europe. The Friars Minor were ardent proponents of devotional meditation as a means to access and understand the Passion. The hours and guides they produced, such as Meditaciones vite Christi (MVC), were widely circulated in Europe.

Necessarily, such devotional literature expanded on the terse accounts of the Via Dolorosa in the Bible; the period of time between just after Christ’s condemnation by Pilate and just before his crucifixion receives no more than a few verses in the four Gospels. Throughout the fourteenth century, a number of events, marked by stations on the Via Dolorosa, emerged in devotional literature and on the physical site in Jerusalem.

The first stations to appear in pilgrimage accounts were the Encounter with Simon of Cyrene and the Daughters of Jerusalem. These were followed by a host of other, more or less ephemeral, stations, such as the House of Veronica, the House of Simon the Pharisee, the House of the Evil Rich Man Who Would Not Give Alms to the Poor, and the House of Herod. In his book, The Stations of the Cross, Herbert Thurston notes: “… Whether we look to the sites which, according to the testimony of travelers, were held in honor in Jerusalem itself, or whether we look to the imitation pilgrimages which were carved in stone or set down in books for the devotion of the faithful at home, we must recognize that there was a complete want of any sort of uniformity in the enumeration of the Stations.”

This negotiation of stations, between the European imagination and the physical site would continue for the next six centuries. Only in the 19th century was there general accord on the position of the first, fourth, fifth, and eighth stations. Ironically, archaeological discoveries in the 20th century now indicate that the early route of the Via Dolorosa on the Western hill was actually a more realistic path.

The equation of the present Via Dolorosa with the biblical route is based on the assumption that the Praetorium was adjacent to the Antonia Fortress. However, like Philo, the late-first-century writer Josephus testifies that the Roman governors of Roman Judaea, who governed from Caesarea Maritima on the coast, stayed in Herod’s Palace while they were in Jerusalem, carried out their judgements on the pavement immediately outside it, and had those found guilty flogged there; Josephus indicates that Herod’s Palace is on the western hill, and it has recently (2001) been rediscovered under a corner of the Jaffa Gate citadel. Furthermore, it is now confirmed by archaeology that prior to Hadrian’s 2nd-century alterations (see Aelia Capitolina), the area adjacent to the Antonia Fortress was a large open-air pool of water.

In 2009, Israeli archaeologist Shimon Gibson found the remains of a large paved courtyard south of the Jaffa Gate between two fortification walls with an outer gate and an inner one leading to a barracks. The courtyard contained a raised platform of around 2 square metres (22 sq ft). A survey of the ruins of the Praetorium, long thought to be the Roman barracks, indicated it was no more than a watchtower. These findings together “correspond perfectly” with the route as described in the Gospels and matched details found in other ancient writings.

The route traced by Gibson begins in a parking lot in the Armenian Quarter, then passes the Ottoman walls of the Old City next to the Tower of David near the Jaffa Gate before turning towards the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. The new research also indicates the crucifixion site is around 20 metres (66 ft) from the traditionally accepted site.

The traditional route starts just inside the Lions’ Gate

(St. Stephen’s Gate) in the Muslim Quarter, at the Umariya Elementary School, near the location of the former Antonia Fortress, and makes its way westward through the Old City to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the Christian Quarter. The current enumeration is partly based on a circular devotional walk, organised by the Franciscans in the 14th century; their devotional route, heading east along the Via Dolorosa (the opposite direction to the usual westward pilgrimage), began and ended at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, also passing through both Gethsemane and Mount Zion during its course.

Whereas the names of many roads in Jerusalem are translated into English, Hebrew, and Arabic for their signs, the name used in Hebrew is Via Dolorosa, transliterated. The Arabic name is the translation of ‘way of pain’.

The first and second stations commemorate the events of Jesus’ encounter with Pontius Pilate, the former in memorial of the biblical account of the trial and Jesus’ subsequent scourging, and the latter in memorial of the Ecce homo speech, attributed by the Gospel of John to Pilate. On the site are three early 19th-century Roman Catholic churches, taking their names from these events; the Church of the Condemnation and Imposition of the Cross, the Church of the Flagellation, and the Church of Ecce Homo; a large area of Roman paving, beneath these structures, was traditionally regarded as Gabbatha or ‘the pavement’ described in the Bible as the location of Pilate’s judgment of Jesus.

However, scholars are now fairly certain that Pilate carried out his judgements at Herod’s Palace at the southwest side of the city, rather than at this point in the city’s northeast corner. Archaeological studies have confirmed that an arch at these two traditional stations was built by Hadrian as the triple-arched gateway of the eastern of two forums. Prior to Hadrian’s construction, the area had been a large open-air pool of water, the Struthion Pool mentioned by Josephus.

When later building works narrowed the Via Dolorosa, the two arches on either side of the central arch became incorporated into a succession of buildings; the Church of Ecce Homo now preserves the northern arch.

The three northern churches were gradually built after the site was partially acquired in 1857 by Marie-Alphonse Ratisbonne, a Jesuit who intended to use it as a base for proselytism against Judaism. The most recent church of the three—the Church of the Flagellation—was built during the 1920s; above the high altar, under the central dome, is a mosaic on a golden ground showing The Crown of Thorns Pierced by Stars, and the church also contains modern stained-glass windows depicting Christ Scourged at the Pillar, Pilate Washing his Hands, and the Freeing of Barabbas. The Convent, which includes the Church of Ecce Homo, was the first part of the complex to be built, and contains the most extensive archaeological remains. Prior to Ratisbonne’s purchase, the site had lain in ruins for many centuries; the Crusaders had previously constructed a set of buildings here, but they were later abandoned.[clarification needed]

Although no such thing is recounted by the canonical Gospels, and no official Christian tenet makes these claims, popular tradition has it that Jesus stumbled three times during his walk along the route; this belief is currently manifested in the identification of the three stations at which these falls occurred. The tradition of the three falls appears to be a faded memory of an earlier belief in The Seven Falls; these were not necessarily literal falls, but rather depictions of Jesus coincidentally being prostrate, or nearly so, during performance of some other activity. In the (then) famous late-15th-century depiction of the Seven Falls, by Adam Krafft, there is only one of the Falls that is actually on the subject of Jesus stumbling under the weight of the cross, the remaining Falls being either encounters with people on the journey, the crucifixion itself, or the removal of the dead body from the cross.

The first fall is represented by the current third station, located at the west end of the eastern fraction of the Via Dolorosa, adjacent to the 19th-century Polish Catholic Chapel; this chapel was constructed by the Armenian Catholics, who though ethnically Armenian, are actually based in Poland. The 1947-48 renovations, to the 19th-century chapel, were carried out with the aid of a large financial grant from the Polish army. The site was previously one of the city’s Turkish baths.

The second fall is represented by the current seventh station, located at a major crossroad junction, adjacent to a Franciscan chapel, built in 1875. In Hadrian’s era, this was the junction of the main cardo (north-south road), with the decumanus (east-west road) which became the Via Dolorosa; the remains of a tetrapylon, which marked this Roman junction, can be seen in the lower level of the Franciscan chapel. Prior to the 16th century, this location was the 8th and last station.

The third fall is represented by the current ninth station, which is not actually located on the Via Dolorosa, instead being located at the entrance to the Ethiopian Orthodox Monastery and the Coptic Orthodox Monastery of Saint Anthony, which together form the roof structure of the subterranean Chapel of Saint Helena in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre; the Coptic and Ethiopian Orthodox churches split in 1959, and prior to that time the monastic buildings were considered a single Monastery. However, in the early 16th century, the third fall was located at the entrance courtyard to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, and an engraved stone cross signifying this remains in situ. Prior to the 15th century, the final station was located before this point would have been reached.

Four stations commemorate encounters between Jesus and other people, in the city streets; one encounter is mentioned in all the Synoptic Gospels, one is mentioned only in the Gospel of Luke, and the remaining two encounters only exist in popular tradition.

The New Testament makes no mention of a meeting between Jesus and his mother, during the walk to his crucifixion, but popular tradition introduces one. The fourth station, the location of a 19th-century Armenian Catholic oratory, commemorates the events of this tradition; a lunette, over the entrance to the chapel, references these events by means of a bas-relief carved by the Polish artist Zieliensky. The oratory, named Our Lady of the Spasm, was built in 1881, but its crypt preserves some archaeological remains from former Byzantine buildings on the site, including a mosaic floor.

The fifth station refers to the biblical episode in which Simon of Cyrene takes Jesus’ cross, and carries it for him. Although this narrative is included in the three Synoptic Gospels, the Gospel of John does not mention Simon of Cyrene but instead emphasizes the portion of the journey during which Jesus carried the cross himself. The current traditional site for the station is located at the east end of the western fraction of the Via Dolorosa, adjacent to the Chapel of Simon of Cyrene, a Franciscan construction built in 1895. An inscription, in the architrave of one of the Chapel doors, references the Synoptic events.

Prior to the 15th century, this location was instead considered to be the House of the Poor Man, and honoured as the fifth station for that reason; the name refers to the Lukan tale of Lazarus and Dives, this Lazarus being a beggar, and Dives being the Latin word for [one who is] Rich. Adjacent to the alleged House of the Poor Man is an arch over the road; the house on the arch was thought to be the corresponding House of the Rich Man. The houses in question, however, only date to the Middle Ages, and the narrative of Lazarus and Dives is now widely held to be a parable.

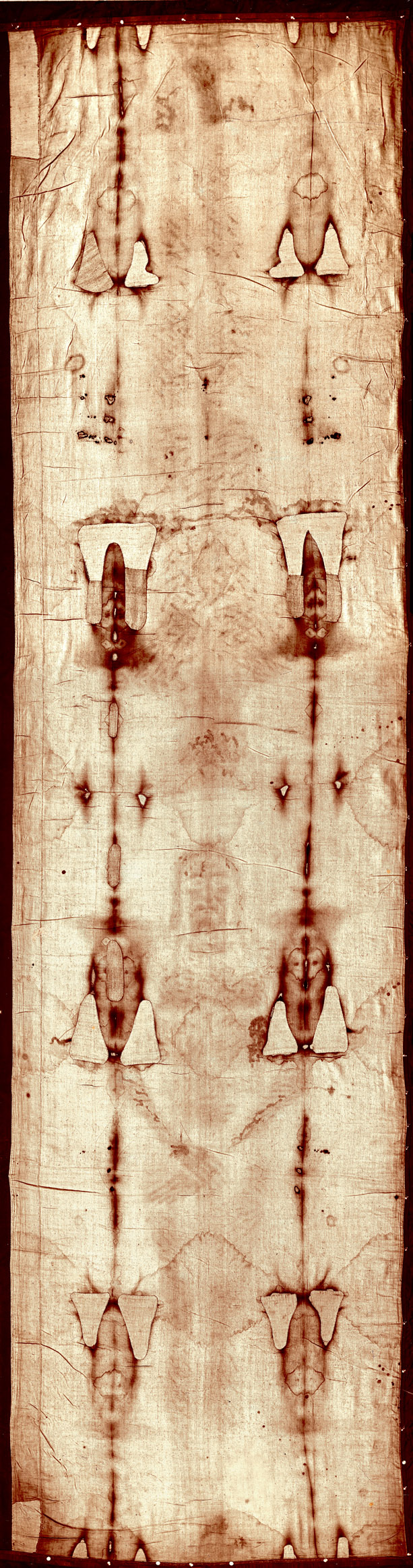

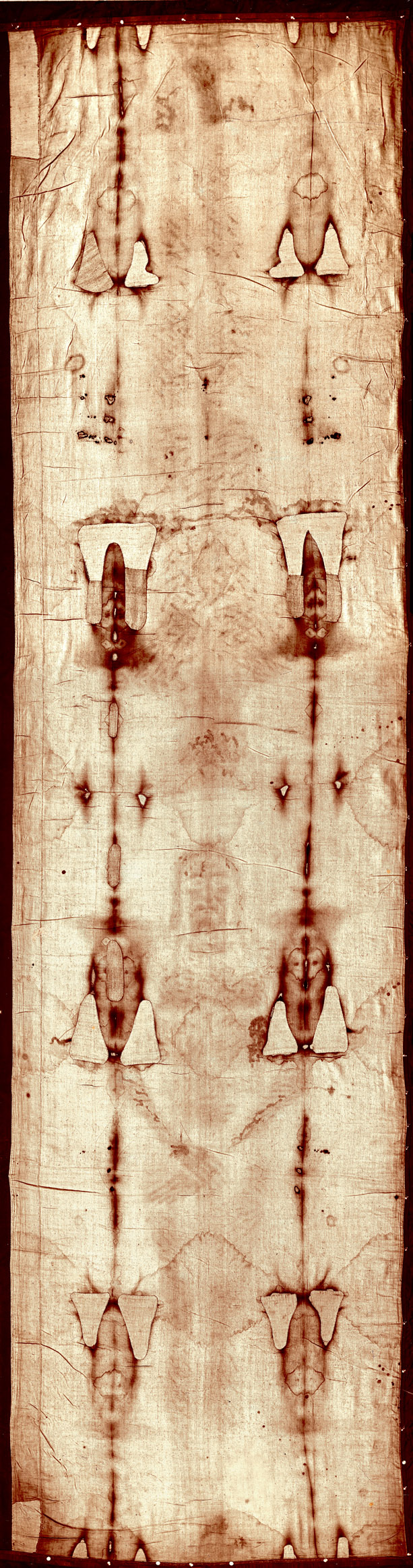

A medieval Roman Catholic legend viewed a specific piece of cloth, known as the Veil of Veronica, as having been supernaturally imprinted with Jesus’ image, by physical contact with Jesus’ face. By metathesis of the Latin words vera icon (meaning true image) into Veronica, it came to be said that the Veil of Veronica had gained its image when a Saint Veronica encountered Jesus, and wiped the sweat from his face with the cloth; no element of this legend is present in the Bible, although the similar Image of Edessa is mentioned in The Epistles of Jesus Christ and Abgarus King of Edessa, a late piece of New Testament apocrypha. The Veil of Veronica relates to a pre-Crucifixion image, and is distinct from the post-Crucifixion Holy Face image, often related to the Shroud of Turin.

The current sixth station of the Via Dolorosa commemorates this legendary encounter between Jesus and Veronica. The location was identified as the site of the encounter in the 19th century; in 1883, Greek Roman Catholics purchased the 12th-century ruins at the location, and built the Church of the Holy Face and Saint Veronica on them, claiming that Veronica had encountered Jesus outside her own house, and that the house had formerly been positioned at this spot. The church includes some of the remains of the 12th-century buildings which had formerly been on the site, including arches from the Crusader-built Monastery of Saint Cosmas. The present building is administered by the Little Sisters of Jesus, and is not generally open to the public.

The Eighth station commemorates an episode described by the Gospel of Luke, alone among the canonical gospels, in which Jesus encounters pious women on his journey, and is able to stop and give a sermon. However, prior to the 15th century the final station in Jesus’ walk was believed to occur at a point earlier on the Via Dolorosa, before this location would have been reached. The present eighth station is adjacent to the Greek Orthodox Monastery of Saint Charalampus; it is marked by the word Nika (a Greek word meaning Victory) carved into the wall, and an embossed cross.

Each Friday, a Roman Catholic procession walks the Via Dolorosa route, starting out at the monastic complex by the first station; the procession is organized by the Franciscans of this monastery, who also lead the procession. Acted re-enactments also regularly take place on the route, ranging from amateur productions with, for example, soldiers wearing plastic helmets and vivid red polyester wraps, to more professional drama with historically accurate clothing and props.

The seat of the Coptic Orthodox Patriarchate in Jerusalem is located on the roof of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. At the entrance of the Patriarchate is a column with a cross on it, marking the 9th Station of the Via Dolorosa. In 1980 Pope Shenouda III of Alexandria (3 August 1923 – 17 March 2012) had forbidden Coptic faithful from traveling to Jerusalem on pilgrimage until the Israeli-Palestinian conflict was resolved. However, despite the ban, dozens of Coptic pilgrims travel to Jerusalem every year, especially during the Easter holidays.

1st Station, Jesus is condemned to death

2nd Station, Jesus carries his cross

3rd Station, Jesus falls the first time

4th Station, Jesus meets his mother

5th Station, Simon of Cyrene helps Jesus carry the cross

6th Station, Veronica wipes the face of Jesus

7th Station, Jesus falls the second time

8th Station, Jesus meets the women of Jerusalem

9th Station, Jesus falls the third time

10th Station, Jesus is stripped of his garments

11th Station, Crucifixion: Jesus is nailed to the cross

12th Station, Jesus dies on the cross

13th Station, Stone of the Anointing

14th Station, Jesus is laid in the tomb

Gates1. Jaffa 2. Zion 3. Dung 4. Golden 5. Lions 6. Herod7. Damascus 8. New (Double, Single, Tanners’)Al-Mawazin

Coordinates: 31°46′45.84″N 35°13′55.46″E / 31.7794000°N 35.2320722°E / 31.7794000; 35.2320722

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Via_Dolorosa